| . |  |

. |

Moscow (RIA Novosti) Aug 12, 2007 The much-publicized polar expedition of Artur Chilingarov, deputy speaker of Russia's State Duma, has eclipsed another event which has a direct bearing on the country's northward expansion. Nobody seems to remember that 75 years ago the ice-breaker Alexander Sibiryakov made a legendary journey along Russia's Northern Sea Route, which connects the Atlantic and Pacific oceans. He was the first to get from Arkhangelsk, on the White Sea in European Russia, to Yokohama, Japan in one go. This was the start of the active exploration of the Arctic. The mission of the Soviet polar expeditions was to confirm our sovereignty over the Arctic North. Otto Schmidt led one of the first and many of the subsequent Arctic expeditions. In 1929-1930 he went to Franz Joseph Land and Severnaya Zemlya (Northern Land). Later, the Alexander Sibiryakov barely made it to the Bering Strait, and the Chelyuskin saga followed a year after. The latter was a heroic, albeit abortive, attempt to follow the same route using an ordinary ship. The Arctic offensive reached its peak with the planting of the red flag in the North Pole and the setting up of the first drifting station there. Polar exploration was moving ahead at a record pace. The Arctic was seen as a limitless source of natural resources and a strategically important route for redeploying naval forces from one ocean to another. Later on, it was viewed as a site for nuclear experiments and ballistic missiles - the distance to America is shorter from there. At that time, the development of territories beyond the Arctic Circle pursued primarily geopolitical and military ends, whereas now, as recent polar expeditions have shown, economic considerations have moved to the fore. Nowadays, the Arctic's main value is its resource-rich seabed. Hydrocarbon reserves in the triangle of ocean claimed by Russia are estimated at 100 billion metric tons of oil equivalent, that is, from a quarter to a third of what is thought to exist in the world. Chilingarov's journey is Russia's second attempt to stake its claim to the arctic El Dorado, and it still has two years to collect information which could allow it to push its maritime border 150 miles to the north. This issue is of paramount importance because it will largely decide what role this country will play in the world in the decades to come. There is not much time left, so Russia is in a hurry. In early May, a research expedition set off on the nuclear-powered ice-breaker Rossiya for a journey from the port of Murmansk to the eastern Arctic. Led by director of the Ocean Studies Institute Valery Kaminsky, 50 geophysicists, underwater geologists and pilots examined the Lomonosov Ridge in detail. They said they had collected encouraging data. Now, having escorted the Russian weather monitoring agency's flagship Academician Fedorov to open water, the Rossiya has made an about-face and started a new journey. It will continue studying the shelf using a remote-controlled Klavesin 1R submersible. It is necessary to collect a sufficient amount of evidence, and expeditions will only be part of the effort. A new drifting station, SP-35, will start operating. Samples of the shelf's soil will probably have to be taken. The Murmansk Shipping Company has suggested converting its nuclear-powered lighter carrier Sevmorput into a drilling ship. In between these two inconspicuous expeditions, Chilingarov made his impressive stunt. What does he have to do with scientific studies? Many domestic and foreign researchers think that the answer is: nothing. Moreover, the samples from the seabed are of no value for geologists. Chilingarov staged a propaganda reality show, with its inevitable suspense, impressive close-ups and mind-boggling effects. It had a definite political subtext, and the great polar explorer was frank about it. "The Arctic is ours and we must prove this by our presence," he said before flying to the north. But he had already proved this when he flew to the North Pole to open the International Polar Year and planted the Russian tricolor in an ice floe. Apparently, he didn't think that was enough. Now he has planted our flag underwater. His previous trips did not receive much attention from the world public, but this one has been met with indignation. State Department Deputy Spokesman Tom Casey told reporters that the flag did not have any legal standing or effect on Russia's seabed claim. Canadian Foreign Minister Peter MacKay recalled: "This isn't the 15th century. You can't go around the world and just plant flags and say, 'We're claiming this territory.'" His Russian counterpart, Sergei Lavrov, parried this challenge by saying: "Nobody is throwing flags around. This is what all pioneers have done." He reminded the Americans of the time they put their stars and stripes on the Moon. The hero of the day used even stronger terms on his return to Moscow: "I don't give a damn what some foreign figures say on this score.... There is the law of the sea, there is the right of 'first night,' and we have used it." But how does the mythical medieval rite compare with an international treaty ratified by Russia? And will Chilingarov's expedition help us boost our claim? Incidentally, President Vladimir Putin reminded Chilingarov that the main thing was to make our claim convincing. In other words, PR stunts are pleasing to the eye but are no substitute for the meticulous research being conducted by anonymous scientists. But the deputy speaker has no time for them. He is getting ready for a new heroic assault on the North Pole - this time he wants to repeat Umberto Nobile's flight on an airship. In so doing he will reaffirm the Russian polar presence in the air - he has already done so on land and underwater. As the song of the Young Pioneers, the Soviet Communist youth organization, goes, "We know of no obstacles on the sea or land, we have no fear of ice and clouds." They promised to "carry the red banner through the worlds and centuries." The banner is now a tricolor, but isn't it the successor to those flags that were planted in the Arctic by the first polar explorers? The opinions expressed in this article are the author's and do not necessarily represent those of RIA Novosti. Community Email This Article Comment On This Article Related Links Beyond the Ice Age

Washington (AFP) Aug 10, 2007

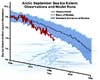

Washington (AFP) Aug 10, 2007Sea ice in the northern hemisphere has plunged to the lowest levels ever measured, a US Arctic specialist said Friday, adding that it was likely part of the long-term trend of polar ice melt driven by global warming. |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2007 - SpaceDaily.AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA Portal Reports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additional copyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |