| . |  |

. |

Toronto ON (SPX) Aug 08, 2005 The embryos of a long-necked, herbivorous dinosaur are the earliest ever recorded for any terrestrial vertebrate and point to how primitive dinosaurs evolved into the largest animals ever to walk on earth, say scientists from the University of Toronto at Mississauga (UTM), the Smithsonian Institution and the University of Witwatersrand, South Africa. The discovery, published in the July 29 issue of Science, provides a rare glimpse into the life of the sauropodomorph dinosaur Massospondylus, an early dinosaur that grew to five metres and was relatively common in South Africa. The 190 million year-old embryos are from the beginning of the Jurassic Period, known as the age of dinosaurs. While the delicate bones of most dinosaur embryos were destroyed over time these embryos are represented by well preserved skeletons, one nicely curled up inside the egg. "The work on the embryo, its identification, and the fact we can see the detailed anatomy of the earliest known dinosaur embryo is extremely exciting," says lead author Robert Reisz, a biology professor at UTM. "Most dinosaur embryos are from the Cretaceous period (146 to 65 millions years ago). There are articulated embryos in the Late Cretaceous, like duck bill dinosaurs and theropods, but those are at least 100 million years younger." According to Reisz, what makes this discovery particularly significant is the ability to put the embryos into a growth series and work out for the first time how these animals grew from a tiny, 15 centimetre embryo into a five metre adult. "This has never been done for a dinosaur. Only Massospondylus is represented by embryos as well as by numerous articulated skeletons of juveniles and adults. The results have major implications for our understanding of how these animals grew and evolved," he says. The Massospondylus hatchling was born four-legged (quadruped), with a relatively short tail, horizontally held neck, long forelimbs and a huge head. As the animal matured, the neck grew faster than the rest of the body but the forelimb and head grew more slowly. The end result was a two-legged animal that looked very different from the four-legged embryo. Reisz says the embryos gives us insight into the origins of the later four-legged giant sauropods, a group that includes the passenger-jet sized Seismosaurus. "Because the embryo of Massospondylus looks like a tiny sauropod with massive limbs and a quadrupedal gait, we proposed in our paper that the sauropod's gait probably evolved through a phenomenon called paedomorphosis, the retention of embryonic and juvenile features in the adult," he says. Another point of great interest is the absence of teeth. "These embryos, which were clearly ready to hatch, had overall awkward body proportions and no mechanism for feeding themselves, which suggest they required parental care," says Reisz. "If this interpretation is correct, we have here the oldest known indication of parental care in the fossil record." While the embryos were discovered in 1978 in South Africa, researchers only now managed to expose the embryos from the surrounding rock and eggshell. U of T research assistant Diane Scott worked on the specimen for a year, using a 100X magnification dissecting microscope and miniature excavating tools. "Diane worked on a steel slab on top of bubble wrap so as not to feel outside vibrations," says Reisz. "Even a door slamming could affect her work." Experts in the field hailed the study as a significant contribution to paleontology. "This discovery is exciting in providing a major piece of the puzzle of how sauropodomorphs grew and reproduced," says Professor James Clark of the Department of Biological Sciences at George Washington University. "In particular it helps to show that this particular primitive sauropodomorph was four-legged when it first hatched and then gradually grew to be two-legged as an adult." Along with Reisz and Scott, the study involved Dr. Hans-Dieter Sues, a paleontologist at the National Museum of Natural History of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, David Evans, a graduate student at UTM, and Michael Raath, a scientist at the University of Witwatersrand. The research was funded by the National Geographic Society, the Natural Sciences and Engineering Council of Canada, the Palaeoanthropology Scientific Trust of South Africa and the University of Toronto. Related Links SpaceDaily Search SpaceDaily Subscribe To SpaceDaily Express  Rockville MD (SPX) Jul 26, 2005

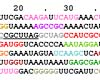

Rockville MD (SPX) Jul 26, 2005At home in the deep, dark Arctic Ocean, the marine bacterium Colwellia psychrerythraea 34H keeps very cool--typically below 5� degrees Celsius. How does the bacterium function in this frigid environment? To find out, scientists at The Institute for Genomic Research (TIGR) and collaborators have sequenced and analyzed C. psychrerythraea's genome. |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2006 - SpaceDaily.AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA PortalReports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additionalcopyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |