| . |  |

. |

Chicago IL (SPX) Feb 23, 2011 The most popular model used by geneticists for the last 35 years to detect the footprints of human evolution may overlook more common subtle changes, a new international study finds. Classic selective sweeps, when a beneficial genetic mutation quickly spreads through the human population, are thought to have been the primary driver of human evolution. But a new computational analysis, published in the February 18, 2011 issue of Science, reveals that such events may have been rare, with little influence on the history of our species. By examining the sequences of nearly 200 human genomes, research led by Ryan Hernandez, PhD, assistant professor of Bioengineering and Therapeutic Sciences at the University of California at San Francisco, found new evidence arguing against selective sweeps as the dominant mode of human adaptation. The reversal suggests that smaller changes in multiple genes may have been the primary driver of changes in human phenotypes, and that new models are needed to retrace the genetic steps of evolution. "Our findings suggest that recent human adaptation has not taken place through the arrival and spread of single changes of large effect, but through shifts of frequency in many places of the genome," said Molly Przeworski, PhD, professor of Human Genetics and Ecology and Evolution at the University of Chicago and co-senior author of the paper. "It suggests that human adaptation, like most common human diseases, has a complex genetic architecture." Under the classic selective sweep model, a new, advantageous gene appears and quickly spreads through the population. Because of its rapid rise, the gene becomes fixed in the genome with less variation than a gene that spread more slowly and was subject to the shuffling effects of recombination. Geneticists have used this model to look for genetic segments surrounded by "troughs" of low variation, the theoretical footprint of a selective sweep. Applying the model has identified more than 2,000 genes - roughly 10 percent of the human genome - suggesting that selective sweeps were a frequent occurrence that drove the evolution of humans away from their primate ancestors. "The selective sweep model was introduced in 1974 and has pretty much been the central model ever since," Przeworski said. "It is fair to say that it is the model behind almost every scan for selection done to date, in humans or in other organisms." However, areas of low diversity around gene segments might also be produced by other evolutionary mechanisms. To test whether selective sweeps were the predominant cause of these troughs, a group of scientists from the University of Chicago, the University of California at San Francisco, Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and the University of Oxford used data from179 subjects in the 1000 Genomes Project, an international effort to catalogue human variation. "This is really a groundbreaking dataset that allowed this type of analysis to be done for the very first time," Hernandez said. The research team looked at genes with human-specific substitutions, where the nucleotide sequence is different from close primate relatives. In some cases, the new sequence switches an amino acid in the protein the gene encodes, a replacement that likely improved the protein's function. In other genes, the sequence change is "synonymous," coding for the same amino acid as before and leaving the protein's function unperturbed. Under the classic selective sweep model, genetic diversity would be lower surrounding the first group of mutations, those that produced beneficial changes in function, because of their quick spread. But when the two groups were compared, the troughs of low diversity were similar for genes that produce functional changes and genes with synonymous substitutions that do not. The result suggests that classic selective sweeps could not have been the most common cause of these low diversity troughs, leaving the door open for other modes of evolution. "Phenotypic variation in humans isn't as simple as we thought it would be," Hernandez said. "The idea that human adaptation might proceed by single changes at the amino acid level is quite a nice idea, and it's great that we have a few concrete examples of where that occurred, but it's too simplistic a view." Further evidence against common selective sweeps was provided by comparing genome variation in different populations. Because Nigerian, European, and Chinese/Japanese populations separated roughly 100,000 years ago and subsequently adapted to different environments, frequent selective sweeps would be expected to fix clear genetic differences between the populations. However, comparing genomes of different populations from the 1000 Genomes Project detected only subtle differences in allele frequencies, representative of small changes over time rather than rapid sweeps. "It dovetails quite well with findings coming out of medical mapping studies, which also suggest that many loci of small effect influence disease risk," Przeworski said. "These findings call into question how much more there is to find using the selective sweep approach, and should also make us skeptical of how many of the findings to date will turn out to be validated." The study, "Classic selective sweeps were rare in recent human evolution," is published in Science on February 18th. In addition to Hernandez and Przeworski, authors include Joanna Kelley and S. Cord Melton of the University of Chicago, Eyal Elyashiv and Guy Sella of Hebrew University of Jerusalem, and Adam Auton and Gil McVean of the University of Oxford. Funding was provided by the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

Share This Article With Planet Earth

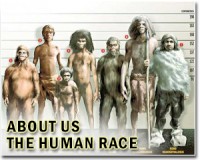

Related Links University of Chicago Medical Center All About Human Beings and How We Got To Be Here

Asian feet made for more than just walking

Asian feet made for more than just walkingHong Kong (AFP) Feb 22, 2011 Most people put one in front of the other as a most basic way to get around, though they often come in handy to kick a ball, ride a bicycle or dance a jig - maybe even walk a tightrope. But in Asia, feet are far more than just the two pins that keep us upright and get us from A to B - they can lead people into a cultural minefield. In India, touching another person's feet is perceived ... read more |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2010 - SpaceDaily. AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA Portal Reports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additional copyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |