| . |  |

. |

Paris (UPI) Mar 29, 2009 The euro crisis may have been resolved by the deal reached with the international Monetary Fund to support the embattled Greeks. But there is one clear and profound result of the deal; the issue of retirement ages and funding for Europe's pensions is now high on the agenda of Europe's governments. The mantra German commentators and radio talk shows kept repeating was that it was simply absurd for Germans to work until they were 67 so Greeks could continue to retire at the age of 62. And the harsh cuts imposed on Greek public spending by their eurozone partners as the price of support mean that Greece cannot afford to continue is current generous pension system. Moreover, a precedent has been established by last week's EU summit that similar harsh terms will be imposed on any other EU government that seeks financial support from its partners. With Portugal, Spain and Italy also facing severe debt problems, very tight squeeze is coming on public spending. This certainly constrains Europe's traditionally generous welfare states. The simplest way to adapt to that strain is to raise the retirement age, particularly for those southern countries that tend both to have the biggest fiscal problems and to start paying pensions earlier. This has already begun in northern Europe. In the 1990s, the traditional retirement age in Italy, France and Germany was 60. This was very early, considering that life expectancy is approaching 80 and that modern diets and medicine allow many people to continue working well into their 70s. An increase of the retirement age to 65, which is being progressively introduced in Germany, would sharply reduce the number of retirees who depend on the employed for support. A retirement age of 70 in Germany would virtually end the problem, at least until life expectancy rose as high as 90 years. The work force participation rate in Germany (and much of continental Europe) is relatively low. Not only do Europeans retire on the early side but the generous social welfare system allows others to withdraw from work earlier in life. An increase in employment would boost revenues flowing into the social security system. For example, only 67 percent of women in Germany were in the work force in 2005, compared with 76 percent in Denmark and 78 percent in Switzerland. (The average rate for the 15 "core" EU states is 64 percent; for the United States, 70 percent.) Professor David Coleman, a demographer at Oxford University, has suggested that the European Union's work force could be increased by nearly one-third if both sexes were to match Denmark's participation rates. The EU itself has set a target participation rate of 70 percent for both sexes. Reaching this goal would significantly alleviate the fiscal challenge of maintaining Europe's welfare system, which has been aptly described as "more of a labor-market challenge than a demographic crisis." The average retirement age across Europe is around 65 for men and women. The lowest is 59 for Italian women; the highest is 67 for Danish men and women. There are some special cases. French train drivers, for example, can retire at 55 with a pension and most countries allow police and fire workers to retire early. And Britain is phasing out its traditional sexist approach, which allows women to retire at 60 while men have to work until 65. But the problem of financing an increasing number of pensioners with fewer people of working age is about to get a great deal worse in Europe. From now on, according to the EU's own statistical service, the population aged 60 years and above will be growing by 2 million people every year for the next 25 years. The growth of the working age population (15-64 years) is slowing fast and will stop altogether in about six years; from then on, this group, who pay the taxes that finance the welfare state, will be shrinking by 1 million to 1.5 million people each year. Societies and economies will have to adapt to this rapidly changing age structure and manage the prospect of political tensions between the tax-paying young and the pension-receiving elderly. And since older people are usually much more likely to vote than the young, governments will handle this issue with great care. The EU Commission last year deployed its Eurobarometer polling system to assess public views on what they called "Intergenerational Solidarity." The main result was that the vast majority of Europeans have a generally positive image of older people, with only 14 percent considering them to be a burden to society. Strikingly, this minority is largest among the elderly. Almost half of all Europeans asked, 49 percent, said they believe governments should make more money available for pensions and care for the elderly. However, they are pessimistic, with 58 percent of respondents saying governments will no longer be able to pay for pensions and care for older people in the future. And 66 percent say governments should make it easier for older people to continue working beyond the normal retirement age, if they so wish. But there was little resentment of the elderly. "Europeans strongly acknowledge the contribution of older people to society, providing financial help for children and grandchildren and acting as volunteers," the Eurobarometer report said. It noted that 75 percent of respondents said the role of the elderly in caring for family members "is not sufficiently appreciated." The elderly, after all, are not an anonymous mass; they are people's parents and grandparents, who have mostly worked hard, paid their taxes and are thought to deserve a decent retirement. But the lesson of the Greek crisis, and of the huge debt burdens that governments have accumulated during the crisis of the past two years, is that the EU's "Intergenerational Solidarity" is going to be tested.

Share This Article With Planet Earth

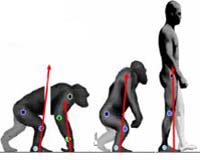

Related Links All About Human Beings and How We Got To Be Here

Program Investigating If And How Past Climate Influenced Human Evolution

Program Investigating If And How Past Climate Influenced Human EvolutionWashington DC (SPX) Mar 08, 2010 Understanding how past climate may have influenced human evolution could be dramatically enhanced by an international cross-disciplinary research program to improve the sparse human fossil and incomplete climate records and examine the link between the two, says a new report from the National Research Council. Climate and fossil records suggest that some events in human evolution - such as ... read more |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2010 - SpaceDaily. AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA Portal Reports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additional copyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |