| . |  |

. |

Washington (AFP) April 11, 2011 Young penguins in the Antarctic may be dying because they are having a tougher time finding food, as melting sea ice cuts back on the tiny fish they eat, US researchers suggested on Monday. Only about 10 percent of baby penguins tagged by researchers are coming back in two to four years to breed, down from 40-50 percent in the 1970s, said the study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. Chinstrap penguins, known for their characteristic head markings that resemble a cap with a black line just under the neck, are the second largest group in the area after the macaroni penguins, and are at particular risk because their population is restricted to one area, the South Shetland Islands. "It is a dramatic change," lead researcher Wayne Trivelpiece, of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's Antarctic Ecosystem Research Division, told AFP. "There are still two to three million chinstrap pairs in this region but there were seven to eight million two decades ago," he said. "There is some concern now. We need to follow these animals and track them." The 30-year study included chinstrap and Adelie penguins in the West Antarctic and tracked the abundance of their main food source, krill, which are the small shrimp-like crustacean mainly eaten by whales, seals and penguins. Trivelpiece was a co-author on a study published in 1992 that suggested penguin populations were surging and subsiding according to changes in sea ice -- with the chinstrap doing better in warm years and the Adelie thriving in cold years. Chinstrap penguins eat and make their nests away from the snow and ice and so are considered ice-avoiding animals, unlike their Adelie counterparts who feed in icy habitats and are seen as more vulnerable when there is less ice. However, Trivelpiece and his co-authors now believe that krill are the real culprit for the disappearing penguin populations, and the damage affects both types of penguins. Krill needs ice to survive, and as climate change causes more polar sea ice to melt, the tiny sea creatures cannot breed or feast on phytoplankton in the ice and their numbers fall, taking away an important source of nourishment for penguins. "Under a scenario of global warming and increasing temperature we had prophesized that Adelies and ice-loving animals like Adelies should decline while chinstraps and ice-avoiding animals should increase," Trivelpiece said. But shortly after the team's paper was published in the early 90s, the data began to change. "From that point shortly thereafter onward, we lost those large fluxes and both species started behaving the same way and both started declining dramatically," he said. "By the time we had enough data to realize what was going on with the youngsters, we realized that the big difference was between the early years when there was a lot of krill around, and the later years when there wasn't." Over the past three decades, krill biomass has declined 38 to 81 percent, said the study. "If warming continues, winter sea-ice may disappear from much of this region and exacerbate krill and penguin declines," it said. The main driver of the decline in krill is climate change, but resurgent numbers of whales -- on the rise after cuts in hunting -- could be increasing the number of predators that eat krill as well, Trivelpiece said. A large commercial fishery that is using the krill for aquaculture feeds could also be cutting back on the natural numbers, the study noted. While the penguins are far from the verge of extinction, the researchers have urged the International Union for the Conservation of Nature to assess their status and possibly bump them higher on Red List of vulnerable species.

Share This Article With Planet Earth

Related Links Water News - Science, Technology and Politics

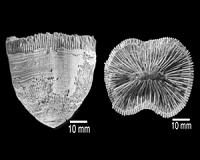

Ancient Corals Provide Insight On The Future Of Caribbean Reefs

Ancient Corals Provide Insight On The Future Of Caribbean ReefsMiami FL (SPX) Apr 11, 2011 Climate change is already widely recognized to be negatively affecting coral reef ecosystems around the world, yet the long-term effects are difficult to predict. University of Miami (UM) scientists are using the geologic record of Caribbean corals to understand how reef ecosystems might respond to climate change expected for this century. The findings are published in the current issue of the j ... read more |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2010 - SpaceDaily. AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA Portal Reports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additional copyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |