| . |  |

. |

Champaign IL (SPX) Feb 13, 2007 Geologists at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign have located a huge chunk of Earth's lithosphere that went missing 15 million years ago. By finding the massive block of errant rock beneath Tibet, the researchers are helping solve a long-standing mystery, and clarifying how continents behave when they collide. The Tibetan Plateau and adjacent Himalayan Mountains were created by the movements of vast tectonic plates that make up Earth's outermost layer of rocks, the lithosphere. About 55 million years ago, the Indian plate crashed into the Eurasian plate, forcing the land to slowly buckle and rise. Containing nearly one-tenth the area of the continental U.S., and averaging 16,000 feet in elevation, the Tibetan Plateau is the world's largest and highest plateau. Tectonic models of Tibet vary greatly, including ideas such as subduction of the Eurasian plate, subduction of the Indian plate, and thickening of the Eurasian lithosphere. According to this last model, the thickened lithosphere became unstable, and a piece broke off and sank into the deep mantle. "While attached, this immense piece of mantle lithosphere under Tibet acted as an anchor, holding the land above in place," said Wang-Ping Chen, a professor of geophysics at the U. of I. "Then, about 15 million years ago, the chain broke and the land rose, further raising the high plateau." Until recently, this tantalizing theory lacked any clear observation to support it. Then doctoral student Tai-Lin (Ellen) Tseng and Chen found the missing anchor. "This remnant of detached lithosphere provides key evidence for a direct connection between continental collision near the surface and deep-seated dynamics in the mantle," Tseng said. "Moreover, mantle dynamics ultimately drives tectonism, so the fate of mantle lithosphere under Tibet is fundamental to understanding the full dynamics of collision." Through a project called Hi-CLIMB -- an integrated study of the Himalayan-Tibetan Continental Lithosphere during Mountain Building, Tseng analyzed seismic signals collected at a number of permanent stations and at many temporary stations to search for the missing mass. Hi-CLIMB created a line of seismic monitoring stations that extended from the plains of India, through Nepal, across the Himalayas and into central Tibet. "With more than 200 station deployments, Hi-CLIMB is the largest broadband (high-resolution) seismic experiment conducted to date," said Chen, who is one of the project's two principal investigators. Using high-resolution seismic profiles recorded at many stations, Tseng precisely measured the velocities of seismic waves traveling beneath the region at depths of 300 to 700 kilometers. Because seismic waves travel faster through colder rock, Tseng was able to discern the positions of detached, cold lithosphere from her data. "We not only found the missing piece of cold lithosphere, but also were able to reconstruct the positions of tectonic plates back to 15 million years ago," Tseng said. "It therefore seems much more likely that instability in the thickening lithosphere was partially responsible for forming the Tibetan Plateau, rather than the wholesale subduction of one of the tectonic plates." Other evidence, including the age and the distribution of volcanic rocks and extrapolation of current ground motion in Tibet, the researchers say, also indicates the remnant lithosphere detached about 15 million years ago. Chen and Tseng present their findings in a paper to appear in the Journal of Geophysical Research. The National Science Foundation funded the work. Email This Article

Related Links  Moss Landing CA (SPX) Feb 12, 2007

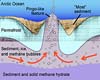

Moss Landing CA (SPX) Feb 12, 2007According to a recent paper published by MBARI geologists and their colleagues, methane gas bubbling through seafloor sediments has created hundreds of low hills on the floor of the Arctic Ocean. These enigmatic features, which can grow up to 40 meters (130 feet) tall and several hundred meters across, have puzzled scientists ever since they were first discovered in the 1940s. |

|

| The content herein, unless otherwise known to be public domain, are Copyright 1995-2006 - SpaceDaily.AFP and UPI Wire Stories are copyright Agence France-Presse and United Press International. ESA PortalReports are copyright European Space Agency. All NASA sourced material is public domain. Additionalcopyrights may apply in whole or part to other bona fide parties. Advertising does not imply endorsement,agreement or approval of any opinions, statements or information provided by SpaceDaily on any Web page published or hosted by SpaceDaily. Privacy Statement |